The Limitations of Origin Determination

In this second instalment of a series of articles on the origin determination of coloured gemstones, the Gubelin Gem Lab Ltd, in Lucerne, Switzerland, focuses on blue sapphires from Sri Lanka and from the Ilakaka region of Madagascar. Gubelin shows here that it is not always possible to determine the origin

of gemstones with absolute certainty.

As we outlined in the first part of this series of articles (see JNA, July 2006, page 66), the most important gemmological-mineralogical criteria used for the characterisation of gemstones are:

• Inclusion features (cavity fillings, growth features, solid inclusions)

• Chemical fingerprinting (major, minor, trace elements)

• Spectral fingerprinting (UV-Vis-NIR range)

• Optical properties (refractive indices, birefringence)

• IR characteristics

• Luminescence behaviour

These gemstone properties are always – directly or indirectly – determined by the genetic environment in which the stone was formed. The genetic environment itself is mainly characterised

by the nature of the host rock; “interactive events” between the host rock and its neighbouring rock units; temperature and pressure conditions; and the composition and nature of solutions/liquids responsible for the dissolution, transport and precipitation of the chemical components involved in crystal growth. In the first part of this series, the case study, “Emeralds from the Colombian Cordillera Oriental and the Santa Terezinha mining region in Goias, Brazil,” illustrated the philosophy and technical aspects of the geographic origin concept. The key consideration was that emeralds originating from these two areas were formed in completely different host rocks. As a logical consequence, the Colombian and the Santa Terezinha emeralds show striking differences in their mineralogical-gemmological features.

At this point, most readers will understand that gemstones originating in different geological environments and localities will display different properties, thus allowing their characterisation and separation. But what of gemstones that were formed in similar genetic environments, even though their geographic regions are located great distances apart? As a first approach to this question, it may be stated that the more similar the genetic environments of two gemstones are, the more similar their mineralogical-gemmological properties will be. To discuss the consequences for geographic origin determination, we will use a case study of blue sapphires originating in the ancient “gem island,” Ceylon/Sri Lanka, and the new “treasure island,” Madagascar. By far the most important factors in determining the origin of blue sapphires are inclusion features and chemical and spectral fingerprinting. Optical properties, IR characteristics and luminescence behaviour are properties of little or no locality-specific importance. In Sri Lanka, there are several sapphire-producing areas of economic interest. It is important to note that despite the fact that Sri Lankan sapphires originate in several secondary deposits in different parts of the island (for example, Ratnapura in the south-west and Elahera in the central region), the mineralogical-gemmological properties of Sri Lankan blue, gem-quality stones submitted for origin determination are relatively homogeneous. It is known today that the source of most gemquality sapphires in Sri Lanka are metamorphic rocks of the gneiss/granulite/charnockite types.

One of the most important gem sources today is without doubt the island of Madagascar. This country has enormous potential for the mining of most gemstone species of current commercial interest. Sapphire and ruby deposits are located in different regions of the country and are related to different types of host rocks. Sapphires found in Madagascar are characterised by high variability and complexity: numerous sapphire deposits related to most different types of host rocks are dispersed over the entire island. Examples are:

1) the basalt-related deposits at the northern tip of the country in the Antsiranana Province;

2) the Andranondambo sapphires hosted by so-called skarn-type rocks in the south-eastern part of the island; and

3) the huge secondary deposits located in the Ilakaka and Andilamena areas (south-west central northeast, respectively). It is assumed that the primary sources for the sapphires found in the secondary deposits are metamorphic rocks (probably representing several types similar to the sapphire host rocks in Sri Lanka). The case study below compares blue sapphires from Sri Lanka with their counterparts from the Ilakaka mining region of Madagascar. It may be assumed that the host rocks for most Sri Lankan blue sapphires and the blue sapphires found in the Ilakaka region are of a similar nature.

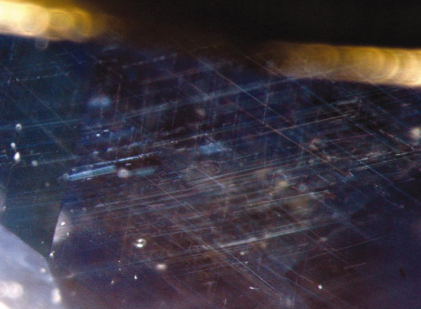

Case study B: Blue sapphires from Sri Lanka and Madagascar (Ilakaka) A basic difference between case study B and case study A (see JNA, July 2006, page 69) is that the emeralds in case study A were found in situ in their host rocks, whereas practically all sapphires in Sri Lanka and a huge part of those in Madagascar originate in so-called secondary deposits (generally in river sediments where they were deposited after having been transported from the places where they were originally formed). For gemstones found in secondary deposits, the study of their mineralogical-gemmological properties allows scientists to trace the stones back to their host rocks and to draw conclusions regarding the nature and type of the host rocks. (1) Inclusion features Numerous different inclusion minerals found in Sri Lankan sapphires are described in the literature. Common in unheated stones is rutile silk composed of long fine threads. Rutile may also be present in the form of coarser needles, “arrowtwins,” brownish-red prisms and rounded platelets. Other guest minerals in Sri Lankan blue sapphires are zircon (wellformed crystals, rounded grains, often surrounded by a small system of fissures), spinel, apatite, mica, feldspar, pyrite/ pyrrhotite, uraninite, hematite and graphite. Heat treatment – especially at high temperatures – will provoke the thermal alteration of most mineral inclusions. In this case, they will typically show a snowball-like appearance.

Often, the altered mineral inclusions are surrounded by atolllike tension/healed fissures. Rutile is the most common inclusion mineral in sapphires from the Ilakaka area. Often, the rutile needles occur in planes or in clouds. They tend to be long and thick and show iridescent colours. Other inclusion minerals identified in Ilakaka sapphires are apatite, feldspar, monazite, zircon, carbonate, graphite and mica. As may be easily seen, most of the inclusion minerals described above have been observed in both Sri Lankan and Ilakaka blue sapphires. It is true that some inclusions seem to be more common in Ilakaka sapphires (for example, monazite or zircon when occurring in groups of transparent rounded crystals) and some in Sri Lankan sapphires (especially uraninite and pyrite). There are also differences in the “rutile scenario” in sapphires from Madagascar and Sri Lanka. However, a clear separation of Sri Lankan and Ilakaka sapphires based on the internal association of inclusion minerals is not always possible. According to some authors, cavities of varying sizes and shapes (often developed as negative crystals) are considered very reliable characteristics of Sri Lankan sapphires. These cavities usually contain fluid fillings. Also quite common is the presence of small black-opaque platelets displaying a metallic lustre (probably graphite). Cavities/negative crystals seem to be less frequent in Ilakaka sapphires, but their presence or absence is certainly not a secure criterion for the separation of sapphires originating in the two localities Further common inclusion features in Sri Lankan blue sapphires are pronounced colour zones, dust bands and abundant healed fissures displaying a wide range of shapes, sizes and patterns. Twinning is considered uncommon in Sri Lankan sapphires. The healed fissures of Ilakaka sapphires also display a large variety of patterns, although these textures are for the most part analogous or identical to those observed in Sri Lankan stones. Colour bands, colour zoning, dust bands and growth structures are the dominant inclusion features in many Ilakaka sapphires.

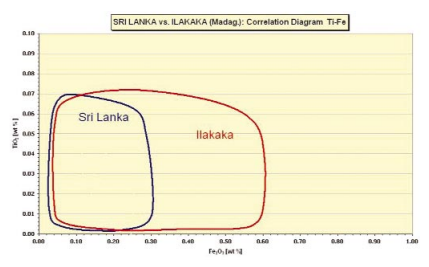

For such inclusions as twin planes, colour zones and dust bands, it may be stated that even though some specific features are more typical of Sri Lankan sapphires and others of Ilakaka sapphires, in many cases these do not provide enough evidence for a clear separation between the two. However, there are inclusion features that point strongly towards a Madagascar (Ilakaka) origin. These include flake-like arrangements (often crystallographically oriented and tubes/fibres (mostly not oriented; normally straight and long; sometimes wavy or bent; often showing some epigenetic alteration. (2) Chemical fingerprinting Generally, the following elements are used for the chemical fingerprinting of sapphires: titanium (Ti), iron (Fe), gallium (Ga), and (with restricted importance) chromium (Cr) and vanadium (V). The iron content of Sri Lankan blue sapphires is considered low to medium (normally below 0.30 weight percent (wt %) Fe2O3). Titanium

shows a large variation, reaching values up to ca. 0.07 wt % TiO2. Gallium is generally low in Sri Lankan blue sapphires (< ca. 0.02 wt % Ga2O3). The elements chromium and vanadium are quite common in Sri Lankan sapphires, including the blue varieties. The upper concentration limit for both elements is, in general, around 0.01 wt % Cr2O3 respective V2O3. The chemical fingerprinting of blue sapphires from Ilakaka may be described as follows. The iron contents show a considerable overlap with Sri Lankan sapphires: ca. 0.05 to 0.60 wt % Fe2O3, compared to ca. 0.05 to 0.30 wt % Fe2O3 for Sri Lankan sapphires

This means higher iron contents are more common in Ilakaka sapphires. For the element titanium, the concentration range in sapphires from both localities is practically identical: from 0.00

to 0.07 wt % TiO2. The situation for gallium is almost the same: for both deposits, the upper concentration limit is normally ca. 0.02 wt % Ga2O3; only rarely are values up to ca. 0.03 wt % measured. The elements chromium and vanadium may also be present in blue sapphires from Ilakaka: V2O3 contents up to ca. 0.03 wt % and Cr2O3 concentrations up to ca. 0.04 wt % have been reported. Some ambiguity remains when using chemical fingerprints for the separation of blue sapphires originating in Sri Lanka from those originating in Ilakaka. There is a substantial overlap of the population fields in practically all of the chemical correlation diagrams (compare, for example, the TiO2 vs. This means that chemical properties alone are of limited help when trying to separate blue sapphires from Sri Lanka and Madagascar. (3) Spectral fingerprinting Sri Lankan blue sapphires show absorption spectra considered typical for corundums originating from a metamorphic environment. They are generally dominated by a broad Fe2+/Ti4+ charge transfer band with maxima at 575 and 700 nm [Figure 7]. The position of the UV absorption edge shows a large variation; Fe3+ absorption groups are generally of low or medium intensity. Absorption bands related to Cr3+ and/or V3+ are normally low; [Fe2+/Fe3+] charge transfer bands are not developed.

Blue sapphires from Ilakaka display a large array of different UV-visNIR absorption spectra. There is no typical “Ilakaka spectrum,” but rather a collection of varying spectra that may also be observed in sapphires originating from other metamorphic sources (such as Sri Lanka, Burma, East Africa or even Kashmir). The fact that the whole spectral variation observed in Sri Lankan blue sapphires is covered by the different types of Ilakaka specs is responsible for the limited value of spectral fingerprinting as a tool for the separation of Madagascan and Sri Lankan sapphires. Case study A showed that the emeralds originating from the two geographic localities in Colombia and Brazil are easily identifiable and separable because their mineralogicalgemmological properties are completely different from each other. This stems from the fact that Colombian and Brazilian emeralds are formed in different geological environments (involving different host rocks, mineralising solutions and pT-conditions, among others). Ambiguity of origin In case study B, presented here, the genetic environments in Sri Lanka and Ilakaka are supposedly quite similar. This means the original host rocks (probably metamorphic rocks of the gneiss, granulite, charnockite types), as well as the growth conditions for the sapphires, should be widely analogous. As a logical consequence, it must be expected that the mineralogical-gemmological properties of the sapphires originating from these environments are also widely overlapping. This assumption is confirmed by the most important criteria used for the characterisation of blue sapphires: 1) internal features; 2) chemical fingerprinting and 3) spectral fingerprinting. It follows that the separation of blue sapphires originating in Sri Lanka from those originating in the Ilakaka mining areas of Madagascar may be very difficult or sometimes even impossible due to their mineralogical-gemmological properties being too similar. Consequently, it is not possible to determine the geographic origin of all blue sapphires from these two deposits with a satisfactory degree of certainty. Some Ilakaka and Sri Lankan sapphires show gemmological characteristics that occur in both sources and thus do not always allow for an unambiguous determination of the origin. This possible ambiguity has consequences for gemmological laboratories doing origin determination: if a gemstone does not show sufficiently clear evidence of one source, the only professional conclusion is to leave the origin undetermined. The case study presented here shows one of the most common examples of when a reliable determination of origin is not possible. However, there are also other sources where gemmological properties such as inclusion features and chemical and spectral fingerprinting overlap to a large extent and cause the same difficulties when trying to determine the origin. The situation raises a number of questions. How does this ambiguity affect the feasibility and credibility of origin determination in gemstones? Should we stop doing origin determination altogether? Or are there ways to manage the challenge and continue to provide the market and the consumer with the information they are asking for: what is the country of origin? As shown here, some gemstones from certain sources lack a single diagnostic inclusion or other property that would allow for the unambiguous determination of their origin. However, the intelligent evaluation and interpretation of the entirety of observed features, combined with additional advanced analysis, does allow us to draw conclusions even in such difficult cases. We will discuss this in more detail in the next article in our series.